© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

Nostalgic Grain: Four Shin Hanga Prints

|

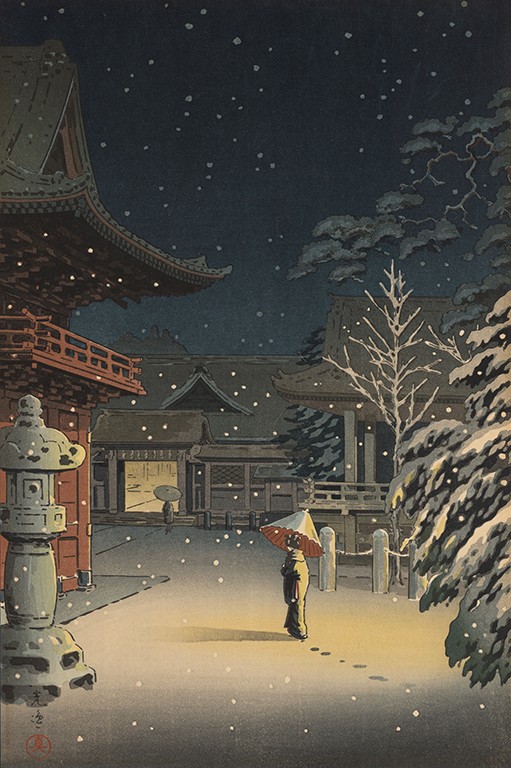

| Detail of Snow at Nezu Shrine, 1934 Tsuchiya Koitsu (Japanese, 1870-1949 Woodblock print on paper; 18 x 13 in. 98.17.5B Gift of Ms. Alice Marshall |

Ready to Print

This past Saturday, Bowers Museum opens its doors to Beyond the Great Wave: Works by Hokusai from the British Museum. As an exhibition of works by one of the most influential artists of all time, it is host to a great many paper prints and books that were created through the traditional Japanese process of woodblock printing. On such an auspicious occasion, it is only fitting that the Bowers Blog would share a selection of Japanese woodblock prints from our own permanent collection, so here we look at four works that were made during the shin-hanga (new prints) movement and either published or influenced in some way by Watanabe Shōzaburō (1885-1962). Of the four works featured in this post, two are by Hasui Kawase (1883-1957) and another two by Koitsu Tsuchiya (1870-1949). A fifth Bowers print by Hiroshige is offered to illustrate the difference between earlier ukiyo-e works.

The distinction between the ukiyo-e (pictures of the floating world) of Japan’s Edo period (1615-1868), the transition towards landscapes championed by Hokusai and other artists towards the end of that same period, and the shin-hanga of the early and mid 20th century has already been touched upon in more detail in What Became of the Floating World.

|

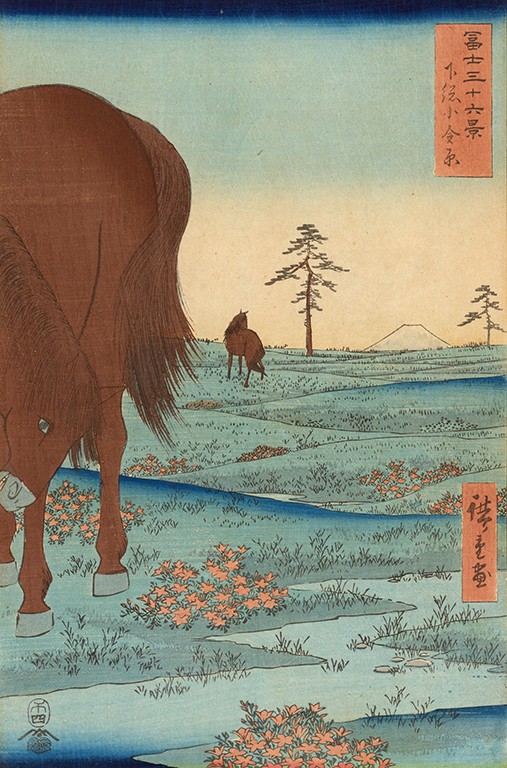

| “Kogane Plain in Shimosa Province” from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, 1858 Hiroshige (Japanese, 1779-1858) Woodblock print on paper; 13 x 8 1/2 in. 2003.38.36 Gift of Mrs. Ramona Ward |

Influencer Extraordinaire

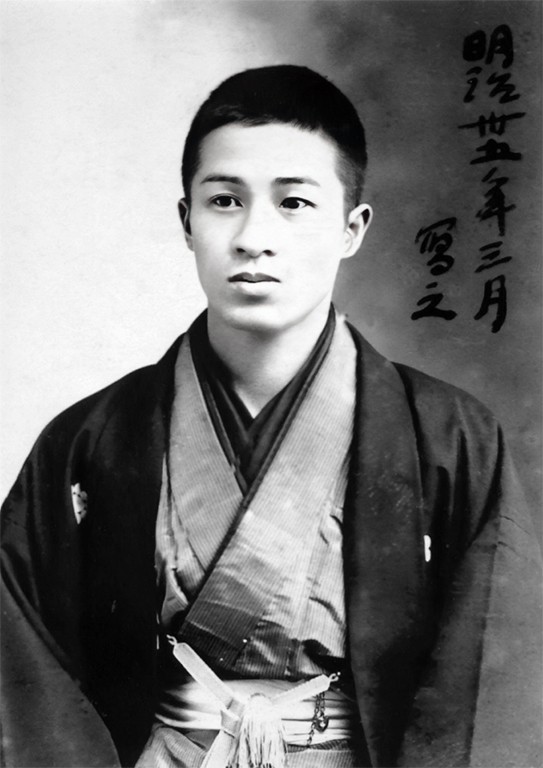

Watanabe Shōzaburō began his career in international exports, only transitioning into the art world after marrying the daughter of a woodblock carver. Using his connections, he started a business that employed the finest carvers and artists that he could find. Though certainly not the first woodblock publisher to do so, he exerted a great degree of control over the subject matter that was created by his artists. Either through his influence or their own studies, his artists’ works became a continuation of what was done by ukiyo-e greats like Hokusai and Hiroshige. Almost all shin-hanga prints fit into the traditional ukiyo-e genres of landscapes, famous places, birds and flowers, beautiful women, and actors. Where the new prints departed from tradition was an increased adherence to western linear perspective—something that Japanese artists had been incorporating into their compositions in various degrees for centuries—and a greater focus on the play of natural phenomena such as light and shadow, reflections, and weather.

|

|

|

| Left to right: Watanabe Shōzaburō, c. 1960; Kawase Hasui, May 1939; Tsuchiya Koitsu, March 1902 | ||

Overseas Audience

Whereas beauty, edification, humor, and a celebration of working peoples were some of the central themes and functions of ukiyo-e works, they were replaced in large part by romanticism and nostalgia in many of the prints produced by Watanabe. Even when the artists that he influenced worked with other publishers, they largely kept the same aesthetic that he had helped cultivate. All four works are haunted by lonely figures navigating inclement but stunningly vivid environs. Despite the changes making the prints less attractive to a domestic audience, they were almost certainly a gambit to make the prints more marketable to a foreign audience he would have been familiar with from his export career. The bet paid off in spades. Artists like Hasui Kawase skyrocketed to international celebrity status within the span of just years.

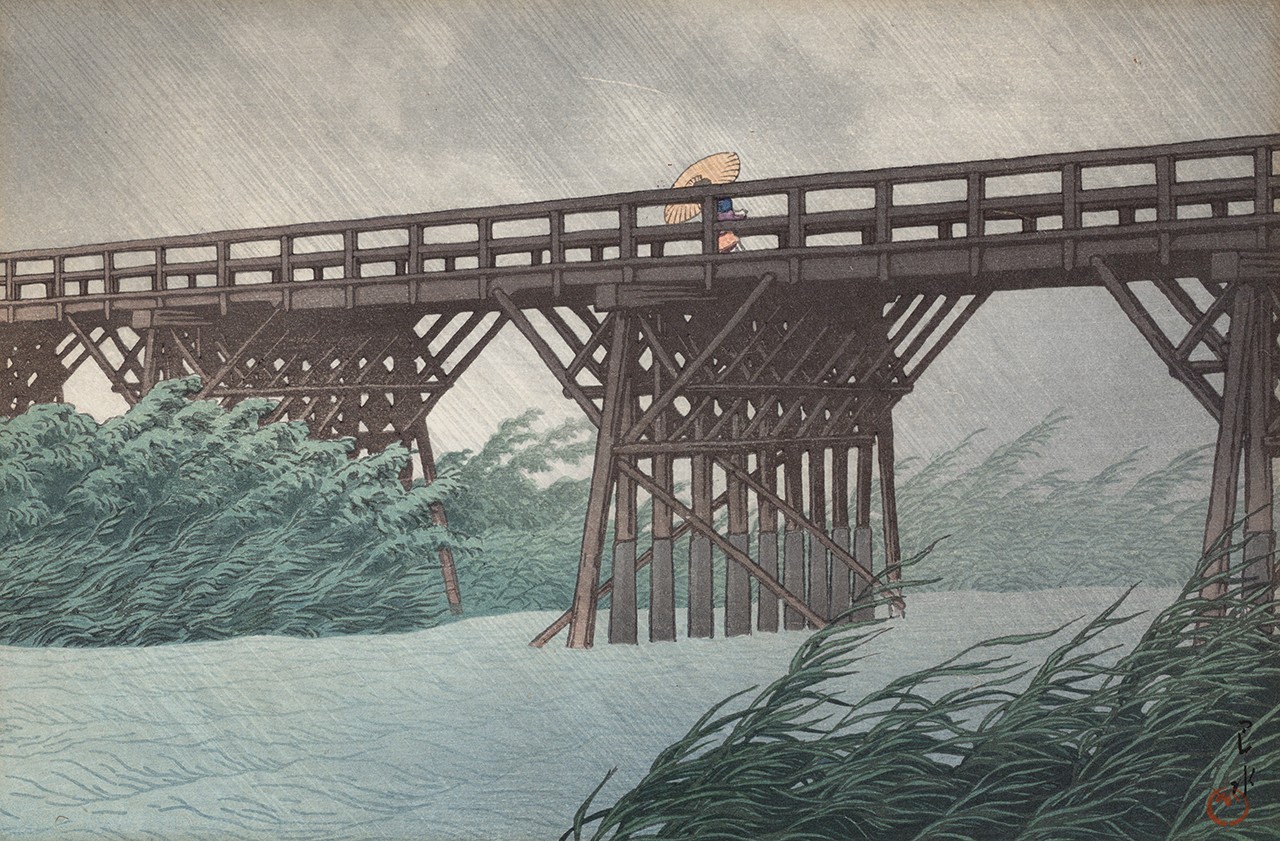

Rain or Shine

In 1918 Hasui Kawase and Watanabe began collaborating on small series of experimental prints and continued to work almost exclusively together until Hasui’s death in 1957. Both of his works in this post are wonderfully atmospheric scenes with heavy downpours captured through a novel technique that had been in part borrowed from Hiroshige prints like “Sudden Shower at Shōno,” from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and in part pioneered by Watanabe. Sudden Shower at Imai Bridge was very likely inspired by Hiroshige’s “Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake,” a beautiful composition that that Van Gogh translated into his Bridge in the Rain. However, in “Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake” as in most Hiroshige works, rain is depicted with a heaviness: thick black lines that bisect the entire print. In the Hasui print we can see that the depiction has a far more atmospheric quality to it.

Nocturne in Wood

Koitsu Tsuchiya began practicing art at an early age, training under some of the great masters of the Meiji period. He met Watanabe in 1931, and the two continued to work together throughout their careers. The two prints by Koitsu in this post were not published by Watanabe, but by Doi Sadaichi, who started his publishing business 15 years after Watanabe had coined the phrase shin-hanga in 1915. Koitsu created a wide variety of prints but focused especially on landscapes and the play of light. Both Snow at Nezu Shrine and Boats at Shinagawa, Night are highly representative of his oeuvre. A lone woman casts her shadow on fresh-fallen snow as she traces a path to the Nezu Shrine complex’s main hall. The men night fishing in Shinagawa bay are lit by moonlight and the warm glow of the fires they are using to attract fish. Just as ukiyo-e prints captured fleeting moments of pleasure, these are images of a Japan that very likely felt to Koitsu that it was at risk of slipping away.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments