© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

Embroidered Worlds: Rebozos of New Spain

|

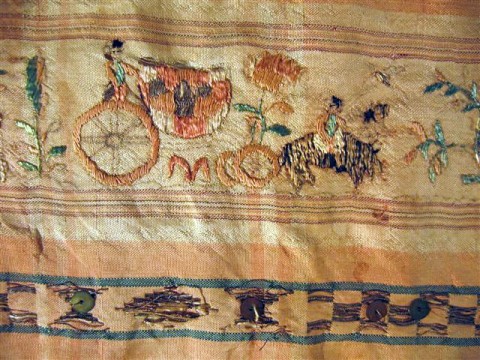

| Detail of Shawl (Rebozo), early 19th Century Unknown Maker; Manila or Mexico City, Viceroyalty of New Spain Silk and sequins; 82 x 30 in. 2379 Gift of Dona Magdalena Murillo |

A Small World After All

We live today in a global society. The produce we eat, the clothes we wear, and the technology we use on a daily basis all might have been produced or assembled halfway across the planet. Though goods have been traded long distances since the earliest stages of human civilization, the era of European colonialism beginning around the end of the 15th century created vast empires where those in power benefitted greatly from long-distance trade. In a continuation of National Embroidery Month, the Bowers Blog explores the larger story of globalization behind a stunning rebozo, or shawl, in the Bowers’ permanent collection.

Trade and Tradition

The Philippines Islands were conquered by Spain in the late 1500s and were controlled by New Spain and later directly by Spain until their independence in 1898. Up until about halfway through the Mexican War of Independence Manila Galleons sailed between Manila and Acapulco once or twice a year. From Acapulco to Manila a relatively direct route could be taken by following the North Equatorial Current. On the return journey the North Pacific Current was picked up just southeast of Japan and followed across the ocean to Alta California where the galleons would stop to rest before picking up the trade winds that would take them to Mexico.

The rebozo seems to have been synthesized from several traditions. Head coverings were worn by women in Spain before Europeans arrived in the Americas, and somewhat similar garments were introduced during the Moorish occupation of Spain. In the Americas, mantles and cloaks like the tilma long predated the arrival of the Spanish. Whatever the case, around 1580 the first rebozos begin to appear in what is today Mexico already bearing some influences of Asian textiles. Though we cannot say for certain where this object was made, the creation of similar styles of shawls in the Philippines was a direct result of the abundant silk brought there from China, traditional textiles from the region, and the influence of Spanish colonizers.

|

| 2379 Gift of Dona Magdalena Murillo |

Textile Tell-Shawl

Documentation on this rebozo’s acquisition is regrettably anecdotal. It was donated to the Bowers within a decade of the Museum’s founding in 1936 by Doña Magdalena Murillo. The story is that in 1812 it and another rebozo were offered for sale in Alta California while a galleon was stopped on its way back to Mexico from Manila. This rebozo was purchased by Patricio Ontivero, Majordomo of Mission San Juan Capistrano and great grandfather of the donor, for 500 heifers and given to his daughter, Georgia, when she was born. Because of the size of the shawl, 82 by 30 inches, it has been surmised by past Bowers curators that the textile was created in the Philippines, that the fabric may have been intended as silk yardage for a dress, and that the embroidery may have become an ongoing project for Georgia or someone else in the family. This might explain why some elements of the textile appear to be unfinished but leaves many questions unresolved.

|

| Shawl (Rebozo), Mexico, late 18th century, silk, embroidered with cotton, silk, and metallic thread Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Mes. George W. Childs Drexel, 1939 1939-1-19. |

Companions in Commonality

The construction of this rebozo is relatively unique compared to other examples despite commonalities in the overall composition of the textile. Its fringed edges might simply be indicative of more wear than the ornate lacework seen in other museum examples—damage to the embroidery floss might be another explanation as to why portions of the piece appear to be unfinished. The rebozo has eight alternating bands containing embroidered figures and designs that represent a wide variety of scenes taken from life. A generally similar rebozo from the Philadelphia Museum of Art corroborates that these thicker, embroidered bands were often separated by thin, multicolored bands, but rather than ikat dyed sections, the separating bands of this textile are sequined.

| Details of 2379 Gift of Dona Magdalena Murillo |

Days in the Field

The real likeness between the Bowers rebozo and those in other museum collections lies in its embroidered vignettes. Boats lazily floating along canals, splendid arbors, elaborately dressed men and women toting parasols, elegant horse-drawn carriages, a wide range of floral motifs, and much, much more are similar in content to other Spanish-American-made rebozos which—like European textiles made around the same time or later French impressionist paintings—illustrate the practice of días de campo, days spent luxuriating in the tamed natural splendor of city parks. The similarities here indicate that its embroidery was either done in or around Mexico City or that an example from that area was used as a reference. If this is the case, then then some elements of the provenance would have to be incorrect aside from just the improbable number of cows that were paid. The most telling evidence here would be the signature, which is present in one corner of the textile, but we have not as of yet been able to discern the name. Either way, the creation of the rebozo alone is indicative of a global network of trade active hundreds of years ago.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments 2

Bayou tapestries.

What a fascinating look at yet another treasure in the Bowers Museum collection that pairs with a current exhibit. The Blog always highlights interesting objects and their artistic and historic value. I only wish some of the items in storage that pair with the Guo Pei exhibit could be displayed for visitors while the exhibit is at Bowers. What another wonderful example of connecting past and present artistic technique.