© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

The Crate Escape: Protecting China’s Cultural Patrimony from Imperial Japan

|

| Crate, 1931-1933 Unknown Maker; Beijing, China Wood and metal; 20 × 36 × 20 1/2 in. 2020.14.111a,b Gift of Anne and Long Shung Shih |

Unsung Heroes

In the context of art museums, transportation solutions for cultural artifacts are generally resigned to storage and staging areas. Visitors to the Bowers will note that our staff—like that of most museums—makes it a point to take objects out of crates and put the crates away before exhibitions open. Every so often, however, a collection earns itself a story of great importance. Films like The Monuments Men have popularized the history of Nazis pillaging and secreting away European museum collections in salt mines and a variety of other repositories. This year there have been several reports of Russian forces looting Ukrainian museums. In such cases, cases themselves can become an important part of history. This is certainly true of the two crates featured here, both made in China to protect its cultural patrimony from Imperial Japan.

|

| Crating the Palace Museum Collection, 1933 |

China: Keep Away Champion 1933-1945

The Palace Museum was established in Beijing’s recently unoccupied Forbidden City in 1925 as a repository for around 1,860,000 cultural artifacts—ancient bronzes, jade artifacts, gold and silver religious icons, paintings, calligraphy, and more—all of which were formerly owned by China’s deposed imperial family. In 1931, Imperial Japan used a false flag operation as an excuse to invade Manchuria. Suspecting that Japan would not stop there, the director of the Palace Museum began planning to crate and move the museum’s most valuable holdings out of Beijing so that they could not be looted. The two crates in this post are among the approximately 13,500 crates made for the Palace Museum’s holdings. An additional 5,500 crates moved sensitive materials from other repositories. In 1933, with Japan pushing south, the crates were brought by carts and then trains to warehouses in Shanghai for three years while the Nationalist government built a new repository for them in Nanjing. As Japanese forces continued to descend southward and took control of Shanghai in November 1937, just 190 miles from Nanjing, the crates again needed to be moved. The subsequent evacuation ranks among the most daring efforts ever undertaken to protect a nation’s artistic heritage. In three shipments, the crates were taken by ship up rivers and rapids, by truck through narrow, snowy mountain passes, and—in rare instances—by hand across muddy terrain, all to find safe storage for them in the farthest western reaches of the country. In 1945 when the war finally ended, most of the works were stored in Leshan, Anshun, and Chongqing.

|

| Crate, 1931-1933 Unknown Maker; Beijing, China Wood and metal; 19 × 35 5/8 × 19 in. 2021.7.3a,b Anonymous Gift |

The Crate Escape Redux

The end of World War II saw the resumption of the Chinese Civil War, a clash between Nationalist and Communist groups. In 1946 and ’47 the crates were returned to Nanjing and again stored in the repository that had been made for them. Seeing that they were losing ground, Chinese Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek began selecting the best of what was stored in Nanjing and shipping it to Taiwan. Ultimately, Mao Zedong was successful in forcing Nationalist forces to retreat to Taiwan, but not before they had taken 3,824 crates with them. In Taiwan, the crates were stored first in the Taichung Sugar Mill warehouse for a few years before being moved to purpose-built storehouses and, following its construction in 1965, the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

|

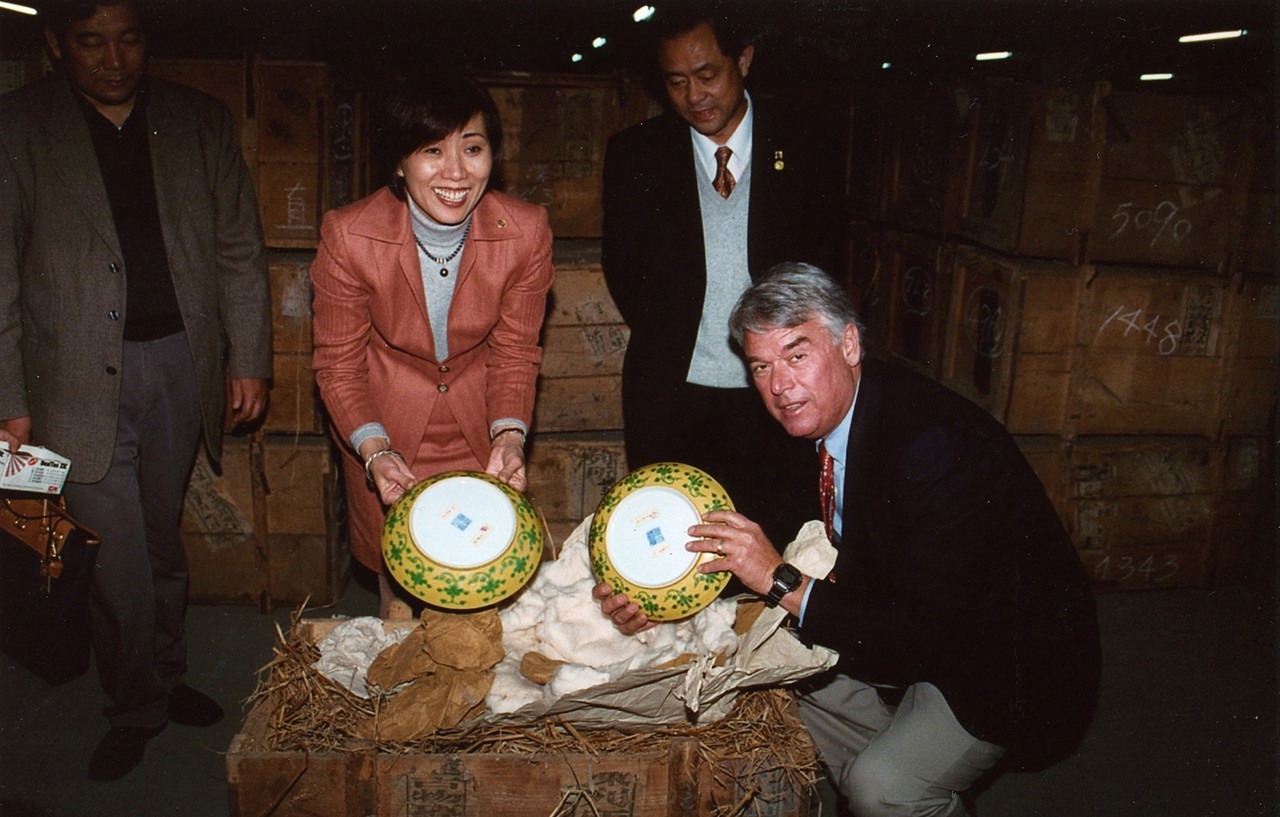

| Peter Keller, Anne Shih, and Palace Museun staff in the Palace Museum's Nanjing Bunker, late 1990s |

Housing Housings

In the late 1990s the Bowers Museum’s late President, Peter Keller, and the current Chair of the Bowers’ Board, Anne Shih, were able to visit the climate-controlled, reinforced cement repository in Nanjing which remained home to the holdings of the Palace Museum not taken by Nationalists. Though the vast majority of the crates beneath Nanjing were returned to the mainland’s Palace Museum in 1950, to this day, there are still approximately 2200 crates in storage there.

|

| Alternate view of 2021.7.3a,b Anonymous Gift |

Packing, but Not Phoning, It In

Though the construction of the crates is unremarkable, the rapid production of around 20,000 units to move these pieces very quickly from the Palace Museum to Nanjing must have been a colossal effort. Packing materials line the interiors and various labels and markings made over the years cover the exteriors. Objects were first wrapped in an amount of wet paper equivalent to half their thickness in order to contour to their shape, then tightly wrapped in hemp ropes, padded with a layer of cotton, and finally inserted into a bed of cotton wadding and rice straw. Remarkably, it is oft repeated that over the course of 16 years of being moved, none of the 20,000 objects stored in these crates were damaged or otherwise lost.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments