© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

The Tooth Tech’s Tiny Tut

|

| Tut Replica, c. 1930 Unknown Photographer Photographic print 99.27.4 Gift of Ms. Katherine Hotchkiss |

Little Mysteries

Having been a collecting institution for almost the past 80 years, the Bowers Museum’s collections are, in some cases, rather eclectic. Whether it’s a wreath made from Victorian-era hair art, a Polynesian breadfruit pounder discovered in the Santa Ana Riverbed or something equally hair-arty or paradoxical, such stories seem to gravitate to the collection. This post is no exception, featuring a miniature model of King Tutankhamun most likely made by Swiss-born American named Claire Doret, but possibly made by an ethereal Hygia May.

Howie Do It

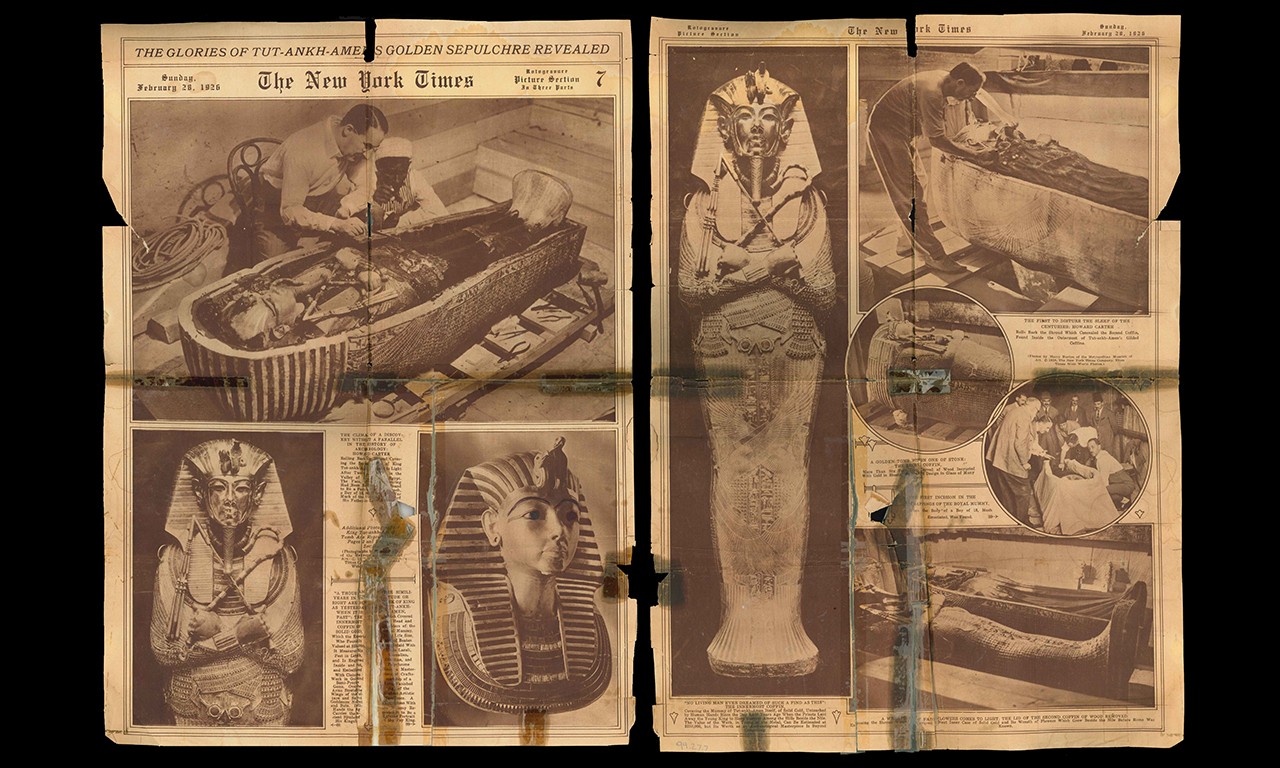

Claire’s obscure tale begins with one of the most famous events of the 20th Century: the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb. On November 4, 1922—after five years of following clues and excavating in Egypt’s Valley of Kings—archaeologist Howard Carter uncovered the front steps of a tomb in an otherwise nondescript desert valley. The door to the tomb was intact and sealed with symbols from Ancient Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty. Carter rushed to the nearest telegraph to excitedly report the good news to the expedition’s sponsor in England, the Earl of Carnarvon. He knew that he was about to walk into something special, but he could never have imagined the impact his discovery would have on the world today.

|

| Replica of the Mummy of King Tut and Sarcophagus, 1930s Claire Doret or Hygia May; Los Angeles, California Ceramic, wood, paint; 13 1/2 X 14 3/4 in. 99.27.1 Gift of Ms. Katherine Hotchkiss |

Short-lived Tutelage

Despite being a household name some three and a quarter millennia after his death and having earned the monosyllabic moniker of “Tut,” Tutankhamun was less famous for his accomplishments in life than for the unplundered status of his tomb. His most significant act was to return Egypt’s religion back to its original orthodoxy after it had been coopted into a vehicle for self-aggrandizement by his father. Unfortunately, Tutankhamun suffered an early death at the age of 19, the cause of which remains a mystery despite extensive scientific investigation. No, the boy pharaoh’s biggest claim to fame is that his tomb was nearly untouched by the thieves who had for years plundered most of the other Egyptian tombs in the Valley of Kings. Though the outer chamber showed signs of some minor break-ins, looters were unable to make off with anything large or penetrate the inner chambers. This meant that the tomb was invaluable for historic study, but after the papers picked up the story the discovery also opened up the world to a new wave of Egyptomania. Tourists and journalists flocked to the tomb in the hopes of getting a glimpse at the treasures and artifacts being excavated. Every few days new articles with images from the tomb were published for the world to see, inspiring the imaginations of many.

|

| The Glories of Tut--Ankh-Amen's Golden Sepulchre Revealed, February 28, 1926 New York Times; New York Paper and ink; 21 7/8 x 15 3/4 in. 99.27.8 Gift of Ms. Katherine Hotchkiss |

Claire-ly Talented

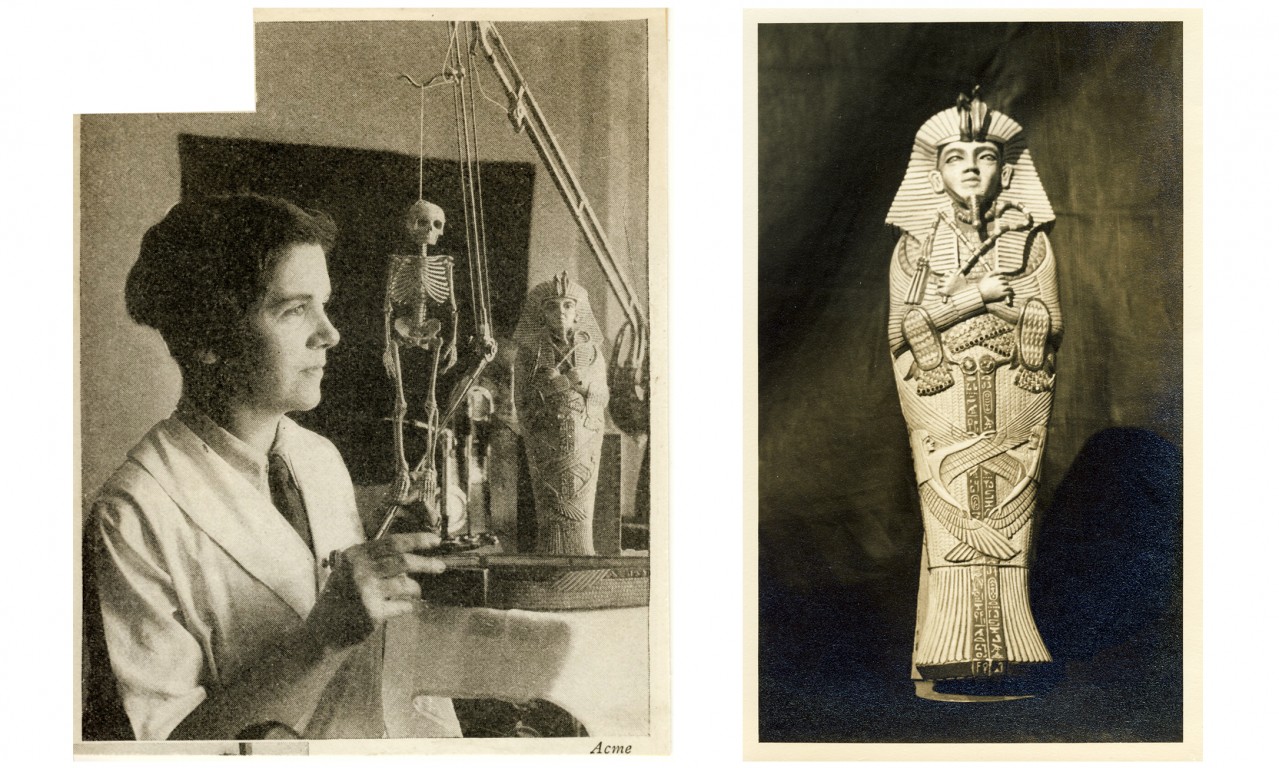

Claire Doret was one such inspired individual. She had moved to Los Angeles from Switzerland in 1920 to work as a dental technician—making her the first female in her profession on the West Coast. A true Renaissance woman, Claire enjoyed painting, sculpting, wood carving and making jewelry. Her unique combination of talents was showcased in 1939, when she filed a patent for a “Tooth Study Model,” made of four separate pieces to show patients different tooth disorders and how they were best fixed. Upon seeing images of King Tut’s tomb, presumably in the 1926 New York Times article pictured above, Claire was mostly likely the person inspired to use her talents to create a miniature replica of Tutankhamun’s innermost sarcophagus. One source indicates that using her dental tools, she painstakingly worked on the piece for years, finally finishing in 1931. The result is this highly detailed and masterfully crafted ceramic sarcophagus and rather than a mummy, an anatomically correct skeleton. Today the model remains one of the quirkier, but well-admired collection items belonging to the Bowers Museum.

|

| Claire Doret with Tut Replica and Replica by Itself, c. 1930 Unknown Photographer Photographic prints 99.27.5-.6 Gift of Ms. Katherine Hotchkiss |

May or May Not

Now, it wouldn’t be a good Bowers Blog post without an element of mystery. While Doret’s name is associated with most of the object’s documentation and clearly photographed with it in the above, in a couple of documents it was noted that the miniature had instead been made by one Hygia May. This includes a document signed by the donor who had presumably known her. So who was the maker? The answer is probably still Claire Doret, but under a nom de plume. It just so happens that Hygia is the Greek goddess of health, the exact kind of material that a polymathic dental technician would be drawn to for a pseudonym; the names rhyme; and it is also worth mentioning that a comprehensive search of California’s 1930 census reveals no information on any Hygia May, but does confirm that Claire Doret was practicing in Los Angeles. While it might not be an enigma on the scale of King Tut’s death, this bite sized case is perhaps fitting for the maker of this model.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments