© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

Tiki Figures: Reflections of Gods and Men

|

| Composite of F81.1.1 (Bowers Museum Purchase) and Village in Taiohae Bay, Nuku Hiva, Marquesas Islands by D Urville (colorized and modified), 1842 |

A Higher Bar

When most Americans hear the word tiki, their mind is transported to the pseudo-Polynesian, pantropical, rum-fueled melting pot that is the American tiki bar. But as American tiki culture enjoys its renaissance, it is important to separate fact and tradition from a synthesized fantasy from the age of exotica. In various parts of Polynesia, the Polynesian term tiki roughly translates to “image” or “depiction,” and is used to refer to carvings of ancestor figures, guardian spirits, or deities made out of wood, stone, or animal parts. When referring to similar figures made in other parts of Polynesia, they go by different names, such as ki’i in Hawai’ian and ti’i in Tahitian. This post looks at three tiki from the Marquesas Islands and looks at how the term may have come to be so prevalently used in the United States.

|

| Figure (Tiki), 19th Century or earlier Nuku Hiva, Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia Stone; 18 × 4 1/2 × 6 in. 98.84.9 Gift of Kristine Moe Shelton and Olise M. Mandat |

Stone Faced

Some of the most recognizable tiki throughout Polynesia are made of stone. Though the mo’ai of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) are called by a different name, they too fall under the larger umbrella of this carving tradition. Large ceremonial complexes in the Marquesas Islands served both religious and secular purposes, and consisted of stone walls, terraces, and platformed structures. Anthropomorphic stone figures such as this one made of red volcanic stone were placed in different parts of sacred areas called me'ae or in a high-roofed house used by priests. There they were used in religious ceremonies during which the gods were honored and consulted. They served to heal the sick and as offerings to the god they invoked. This particular sculpture was collected from Nuku Hiva, the largest of the Marquesas, on September 17, 1936 by Fred E. Lewis, Fred Moe Sr., and Fred Moe Jr. during a trip around Polynesia in Lewis' motorship, the M. S. Stranger.

|

| Stilt-step (Tapuva'e), 20th Century Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia, Polynesia Ironwood; 14 × 3 × 5 in. F81.1.1 Bowers Museum Purchase |

Stepping Up To the Competition

The up-curved shape of this single stilt-step is supported by a tiki figure. Men in the Marquesas Islands often performed on stilts for both rituals and entertainment. Footrests such as this one would be attached to a pole measuring up to seven feet high. Many of these performances were actual contests between men who would compete on stilts in races and in mock battles that tested both their physical and spiritual strength. This representation with the figure holding its belly is very commonplace—it is difficult to tell looking at the eroded stone statue above, but it too is very likely in the same pose. It was believed by Marquesas Islanders that the stomach was a repository for ancestral and ritual knowledge.

|

| Ceremonial War Club (U'u), 19th Century Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia, Polynesia Wood; 41 3/8 × 4 1/2 × 4 in. 93.63.26 Gift of Dr. Ronald W. Jue and Naomi Jue |

Protective Figures

This long ceremonial war club called an u’u is the most well-known of Marquesan warrior clubs. The top is saddle shaped to fit under the arm of the owner when not in use. The intricate low-relief and patterned design carved on this club is typical of the Marquesas Islands. The tiki carved into the head and upper shaft of the club were meant to offer protection to the warrior. It is widely believed that the detailed patterned designs of Marquesan art directly relate to the tattoos that covered the bodies of both men and women.

|

|

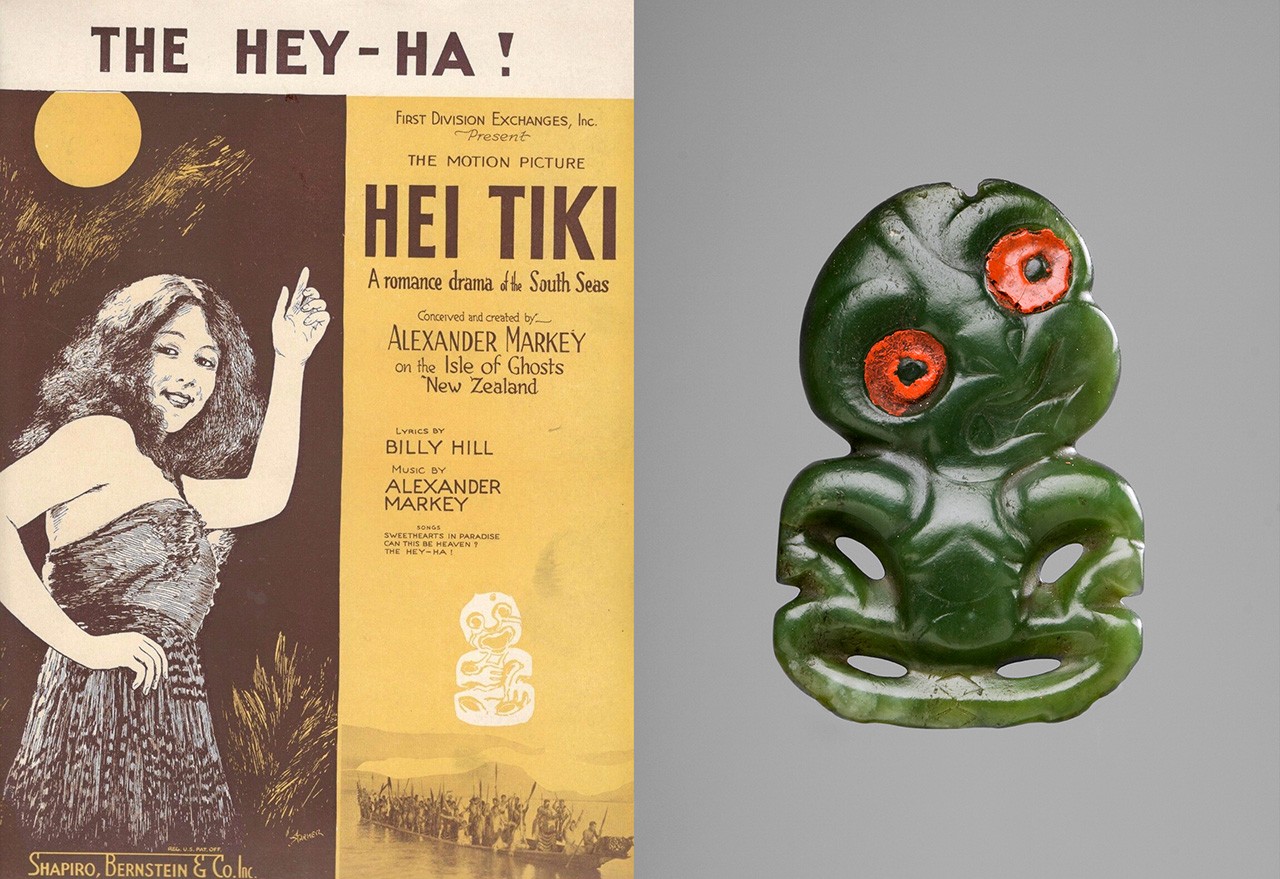

| Sheet music cover for Hei Tiki film, c. 1935 | Amulet (Hei Tiki), 18th Century Māori culture; New Zealand, Polynesia, Oceania Nephrite and sealing wax; 3 × 2 × 1/2 in. 2009.10.1 Bowers Museum Purchase |

Misconstrued

How the word tiki came to be the name of choice for all things either coming from Polynesia or purporting to is itself a fascinating, open-ended story. Interest in Polynesia had been on a slow, consistent rise in the United States ever since the first the first accounts of tropical island paradises reached Anglo ears at the start of the 19th century with stories from explorers and whalers. In 1934 Don the Beachcomber opened in Hollywood. We know it today as the first tiki bar, but it was not until the 1950s that the first of these Polynesian watering holes started to self-identify by the phrase. Perhaps the earliest mainstream use of the word tiki came in the form of a 1935 staged documentary film titled Hei Tiki, which was named after the jade tiki traditionally worn around necks of Māori men and women. Another possible source of popularity for the term may have been Thor Heyerdahl’s 1947 Kon-Tiki expedition in which he sailed a rudimentary raft from Peru deep into island Polynesia in an attempt to prove a scientifically unsound theory about Polynesia having been peopled by the “neolithic Tiki peoples” of South America. Perhaps it was G.I.s returning from the Pacific theater having seen a prevalence of actual tiki carvings. Whatever the case, by the mid 20th century tiki bars were well established in the United States.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments