© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

To Catch a Demon: Mesopotamian Incantation Bowls

|

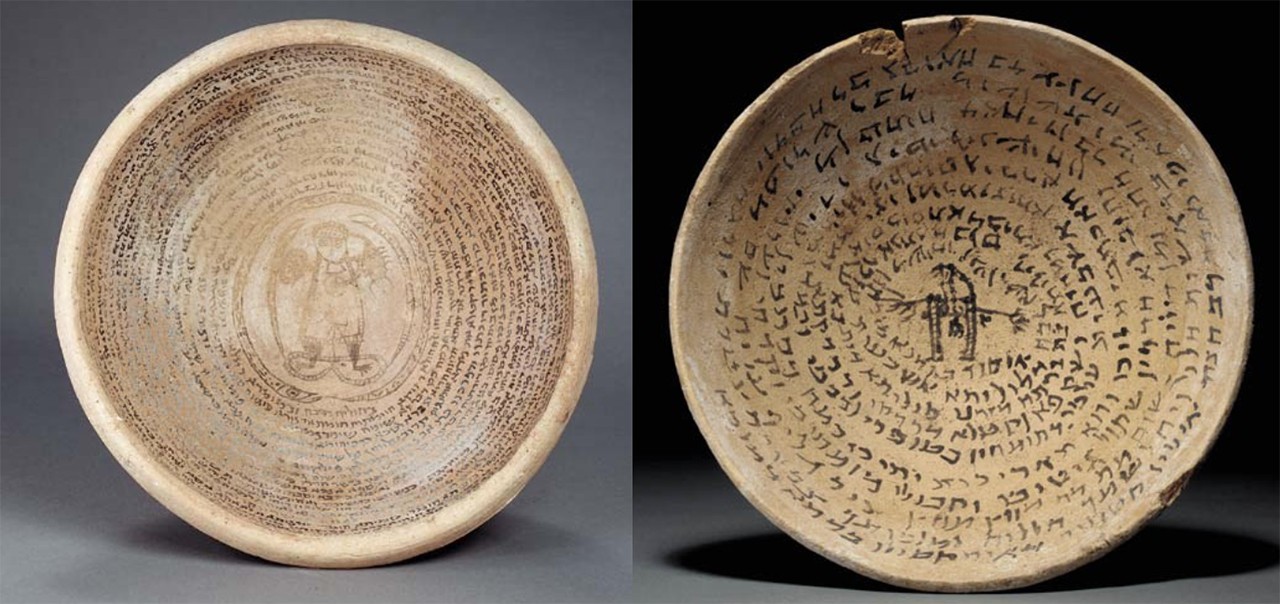

| Incantation Bowl, 4th to 7th Century Unrecorded artist, Sasanian culture; Babylon Governorate, Iraq Ceramic; 10 in. 30892 Gift of Mrs. Charles K. Baldwin |

World of Magic

Magic is a subject that is often broached on the Bowers Blog, as almost all cultures believe in ritual practices that allow us to control aspects of our chaotic world. In the 1850s, the first photographs of incantation bowls originating from western Mesopotamia’s 5th to 7th century were published, beginning a period of study for these pieces as more and more began to surface from colonial archaeological activities. The bowls themselves are wonderful reminders of what we as a species have in common with one another. The words that circle around their interiors are seals of protection for the owner and their loved ones, wards against demons that call upon the gods of multiple religious traditions in a curiously agnostic hope that some deity will answer the call. In this post we look at the Sasanian Empire that these bowls originated from and explore an incantation bowl from the Bowers permanent collection.

Post Parthian Expression

At its height, the Sasanian Empire controlled most of the Middle East north of modern-day Saudi Arabia and east of modern-day Syria. Founded in 224 CE shortly after the fall of the Parthian Empire, the four centuries of the empire’s reign constituted a Golden Age for the Persian people of Iran and was the last period before the spread of Islam throughout the region. If America is a melting pot of religions and cultures, the same could be said of this era in the Middle East. Sasanian shahs changed their policies on religious tolerance to match their personal beliefs and political ambitions, but for the most part individuals were open to practice what they wanted. Christians, Jews, Mandeans, Zoroastrians, and other religious groups all coexisted in ways that were both harmonious and disastrous. All of these groups appear in the texts of incantation bowls, and the deities of each pantheon were called upon, sometimes alongside one another, to aid the individual that commissioned the piece. After the fall of the Sasanian Empire and rise of the Islamic caliphates, the bowls continued to be employed until both they and their associated cult practice disappeared in the 7th century.

|

| Incantation bowl with Aramaic Inscription, 5th–6th century CE, Sasanian culture, Mesopotamia. Metropolitan Museum of Art Collection (86.11.260) |

Debatably Elephantine

The physical properties of these bowls can tell us a little about their manufacture. They were made from clay, a prevalent medium in Mesopotamia dating back as far as 9000 BCE, using a pottery wheel. The shape and size of these bowls could vary widely with examples taking the convex curve seen in the Bowers incantation bowl or the concave curve of the above example from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection. The bowls tended to measure around four to six inches in diameter, but this example is larger, about 10 inches across, which puts it in a subset of incantation bowls called “elephant bowls.” Characters spiral around the interior of the bowl. Inked with a petroleum derivative, they have all but disappeared from portions of the object. The fading of the characters is consistent with a great many of the bowls in museum collections, many of which are now almost illegible without imaging technology. It has been surmised that the bowls would have been commissioned by those referenced in the texts, but that the writing would have been done by scribes or those adept at magic.

|

| Two 7th century Mesopotamian incantation bowls featuring demons, possibly Lilith, from Christie's auctions. |

Cult of Lilith

The Bowers bowl was one of a pair that was unearthed during an excavation of a building’s foundation at the ancient city of Babylon in 1947. They were purportedly found upside-down in sand under a deposit of some two feet of river silt. Based on notes that were donated along with the bowl, the writing is in Aramaic. Due to the fading of the characters, it cannot be meaningfully translated, but it does contain references to female nightmare demons of Mesopotamian origin known as lilitu. Lilitu had a bad reputation for roasting their victims, generally children and infants. As these demons were adopted into the Christian and Jewish traditions, the class of demons amalgamated in Lilith, a biblical figure that is best known as the first wife of Adam and a card-carrying member of the Satanic court.

|

| Detail of 30892 Gift of Mrs. Charles K. Baldwin |

Deadliest Catch

Generally speaking, the incantations could do a number of things: healing fevers and diseases; guarding from sudden death, injustice, and treachery; and exorcising evil spirits. Similar metal talismans were made around the same time and filled largely the same role. Where they differ is that in many instances the bowls called upon deities or angels to ensnare demons. It is believed from drawings on incantation bowls depicting ensnared creatures that the reason that so many have been found upside-down is that they were intended to be traps for careless or curious demons.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments