© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

Kept in Suspense: The Samban of the Iatmul

|

| Suspension Hook (Samban), c. 1930 Iatmul culture; Suapmeri Village, Middle Sepik River region, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea, Melanesia, Oceania Wood and pigment; 25 1/4 × 14 1/2 × 4 in. 2017.1.1 Bowers Museum Purchase |

Whoa Black Betty, Tshambwan

Save perhaps for weekend trips to big box Swedish furniture stores, we generally do not spend much time thinking about storage concerns. Thousands of miles away along Papua New Guinea’s Sepik River though, questions of where to keep one’s belongings are significantly more complicated than whether one should stop for a meatball lunch. In this post the Bowers Blog looks at the suspension hooks or samban (sometimes tshambwan) of the Iatmul people of Papua New Guinea’s Middle Sepik River region, exploring how they are used and their symbolic meaning, and taking a look at two suspension hooks acquired by the Bowers Museum in the past five years.

|

| Suspension Hook (Samban), c. 1925 Iatmul culture; Nyarangai Village, Middle Sepik River region, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea, Melanesia, Oceania Wood; 19 x 5 x 2 1/2 in. 2013.1.1 Bowers Museum Purchase |

Pest Proof

The origin for the Iatmul suspension hooks carved exclusively by male carvers lies in their most basic utilitarian function: suspending food and other valuables in the air so that they are inaccessible to New Guinea’s small mammaloid scavengers or entrepreneurial, grounded insects. These items are held in the characteristic fiber-woven bilum bags found throughout much of New Guinea. Most every home would have at least one hook for storage, but suspension hooks were also signature features of the large ceremonial men’s houses which stand as the locus of Iatmul villages.

|

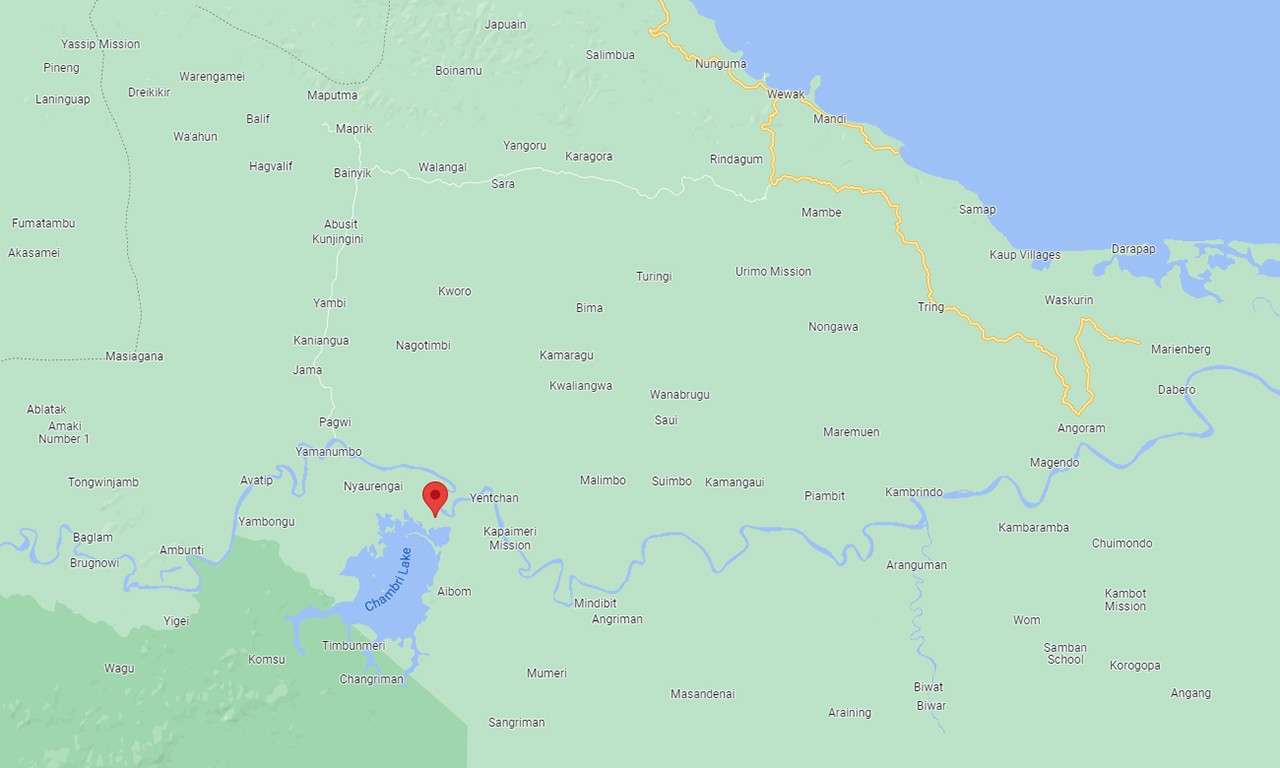

| Location of Suapmeri in the northeast of Papua New Guinea |

Waken, the Spirits

In addition to simple storage, suspension hooks depicting male or female ancestor figures were also used as mediums for communicating with the spirits of one’s elders. In this regard, the location where the samban was used greatly affected its primary function. Suspension hooks which were kept in homes tended to be used just for storage, only rarely if ever consulted for mundane issues. Hooks kept in men’s houses on the other hand almost exclusively served a ceremonial function. These could simply be ancestor figures as is the case of both of the examples shown in this post, or they could embody the Iatmul’s most powerful waken spirits. These figures would regularly be consulted in advance of a hunt or battle through their attendants. Offerings of food would be presented to these powerful suspension hooks and the attendants would consume them, in doing so becoming possessed with the samban’s spirit.

|

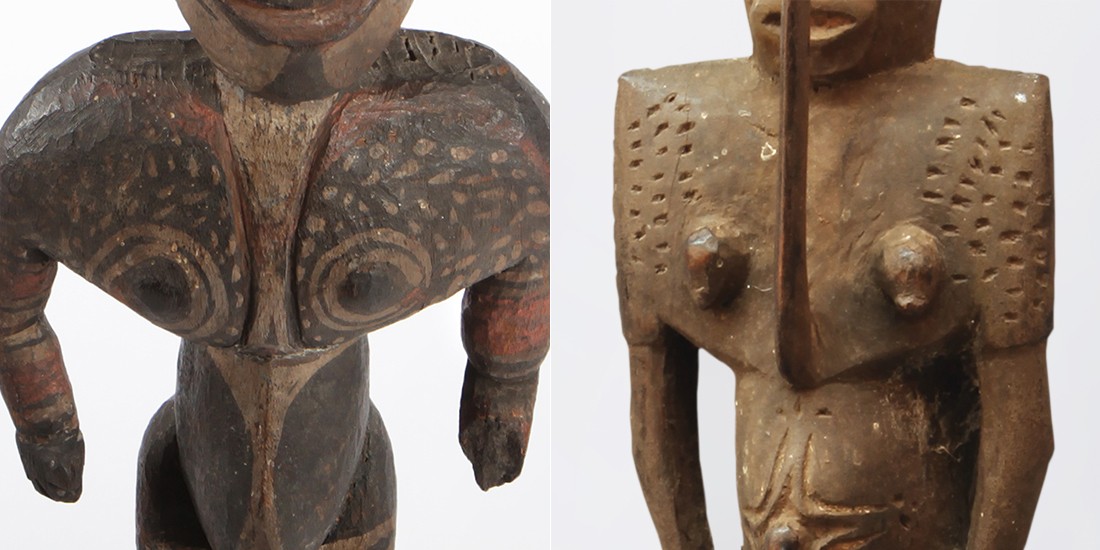

| Detail of the scarification on 2017.1.1 versus the scarification on 2013.1.1. |

Scarred Wood

For a culture that does not have a word for art, the wood carvings of the Iatmul certainly do not lack in decoration. Samban almost always take the form of an ancestor figure and perhaps the most noticeable feature of the Bowers’ hooks is the scarification seen dotting the chests and backs of these objects. On the polychrome suspension hook this is manifested as the small patches of negative space in the sections of black pigment and in the other as small incisions. Scarification, the ritual scarring of one’s body, is practiced among the Iatmul exclusively by initiated men. It represents that they have been swallowed by the crocodilian ancestors and spit out, an action which leaves the same markings covering their own bodies. While this immediately makes sense for the male suspension hook, it requires some explanation for the female samban. Whereas male figures are almost always scarred, female figures tend to show scarification marks only when they represent the most powerful female ancestor spirts. Similar examples of important female figures on suspension hooks are generally found in men’s houses where they are used to store sago cakes. Unfortunately, there has been little scholarship on the crescent or angular u-shape that figures of these hooks rest on aside from noting their functional importance.

Compelling Hook

The story of how the polychrome suspension hook was field collected is also a fascinating one. As is so often the case with Oceanic objects, little is known about the carver. The samban was field collected years later in 1970, most likely by Lynda Cunningham. Cunningham was born in 1943 and held an immense interest in studying cultures before contact with Western society had permanently affected their culture. She took a job as a stewardess for American Airlines and used her position to travel to Papua New Guinea and begin collecting objects from Papua New Guinea in 1966. For the next 25 years she travelled back and forth between New Guinea and New York where she ran a small bookstore and gallery called Oceanic Primitive Arts. The other was field collected in Nyauangai village in 1971. Its owner explained that the spiraling eyes were whirlpools where along the Sepik River it is believed ancestor spirits dwell.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments