© 2023 Kreativa. All rights reserved. Powered by JoomShaper

Prohibition on Flying: The Ungroundable “Wrong Way” Corrigan

|

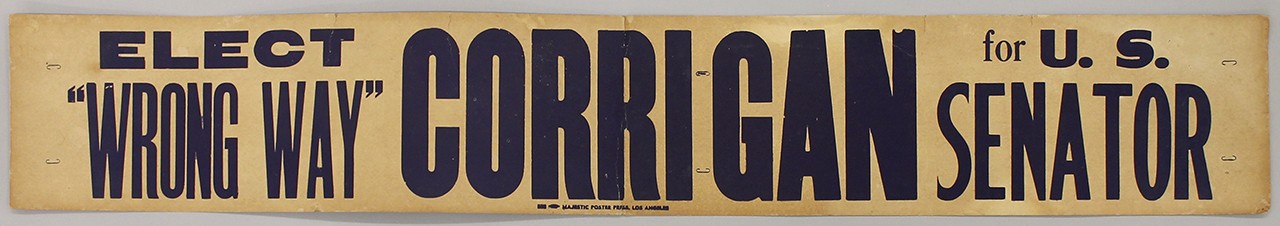

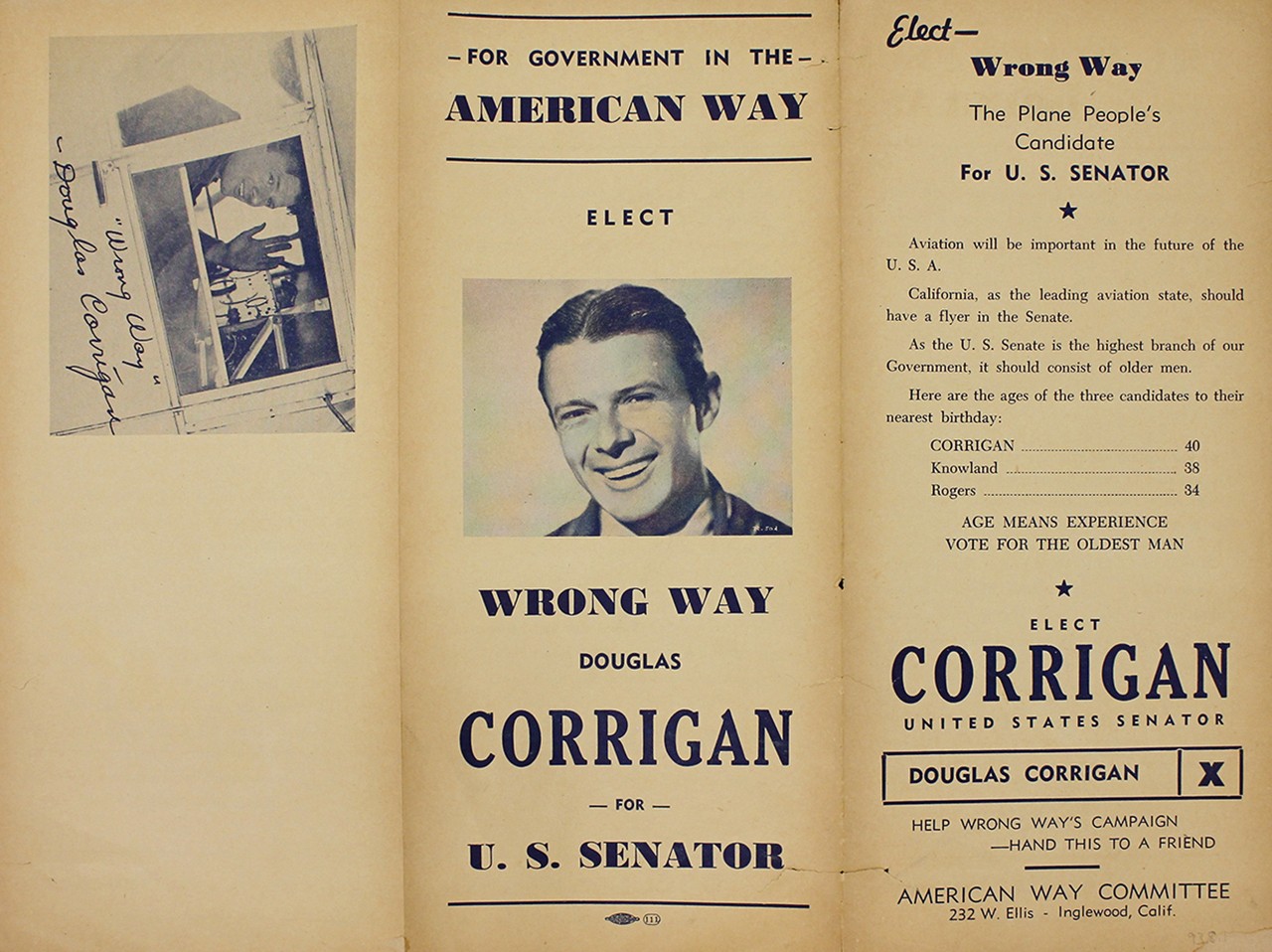

| Edited Campaign Poster for Douglas Corrigan, 1946 American Way Committee and Majestic Poster Press; Inglewood, California Paper and ink; 11 x 14 in. 93.8.2 Gift of Ms. Rosamond Markin |

St. Patrick’s Day Airshow

A day most often paired with green beer, statistically improbable displays of four-leaf clovers, and desperate wishes that the pinch-happy among us would leave their hands to themselves, Saint Patrick’s Day remains at its core a celebration of Irish heritage. In previous years the Bowers Blog has looked at many different aspects of the day including famous Irish Orange Countians such as Thomas J. Scully. Today’s Saint Patrick’s Day post does the same, telling the story of “Wrong Way” Douglas Corrigan, a Santa Ana local and early aviator famous for inadvertently crossing the Atlantic, at least according to his own account.

|

| Campaign Banner for Douglas Corrigan, 1946 American Way Committee and Majestic Poster Press; Inglewood, California Paper and ink; 7 x 46 in. 93.8.3 Gift of Ms. Rosamond Markin |

Son of the Spirit of St. Louis

Clyde Gross Corrigan was born to parents of Irish descent in Galveston, Texas on January 22, 1907. At a young age his mother divorced his father and moved the family to California. He was only 18 when he paid $2.50 for his first flight in a Curtiss JN-4 "Jenny" biplane and in return was bit by the flying bug. A year later he applied to work at Ryan Aeronautical Company and was one of a team of people who assembled the Spirit of St. Louis, the airplane in which Charles Lindbergh famously made the first transatlantic flight. Much of his early life was spent working in aeronautics both as a mechanic and a pilot. All the while he was getting in more experience and preparing to realize two aspirations.

|

| "Wrong Way" Corrigan's plane, Sunshine, arriving in New York via steamship, 1938 |

Luck of the Irish

At the confluence of Corrigan’s dream of making a successful transatlantic traversal and of visiting the country that his family had hailed from less than a century before was his desire to fly to Ireland in a plane of his own modification. In 1933 he purchased a beat-up Curtis-Robin J-1 for $310 and set to work readying it for the almost 3,200 mi journey he planned to take it on. Significant modifications had to be made to his plane, dubbed Sunshine, including installing a 165hp Wright J-6-5 Whirlwind engine. In 1935 he applied for a permit to cross the Atlantic Ocean and was denied by the Bureau of Air Commerce. The engine severely reduced visibility and various home repairs did not meet the relatively lax safety standards of the day. However, he was permitted to make a transcontinental flight, which he did in 1938 from California to New York. With the proper permissions secured for a return flight to California, on July 17 he took to the skies and reappeared just over 28 hours later on a runway in Dublin. His celebrity arrived almost before his punishment could be doled out, resulting in a slap on the wrist and a lifetime of fame. By the time he arrived back in the U.S. aboard a steamship he was already being hailed as “Wrong Way” Corrigan for his insistence, up until his dying day, that his flight to Ireland had been little more than a navigational error.

|

| Campaign Flyer for Douglas Corrigan, 1946 American Way Committee and Majestic Poster Press; Inglewood, California Paper and ink; 12 x 9 in. 93.8.1 Gift of Ms. Rosamond Markin |

The American Way

The objects in the Bowers collection all pertain to Corrigan’s run for U.S. Senate in 1946, just a year after the end of World War II. Though he did not enlist during the war and was too old for the draft, Corrigan worked as a civil service pilot for the U.S. Army Ferry Command. His public appeal and status as an everyman who had worked odd jobs from carpenter to soda water bottler made him an ideal candidate in the minds of the Prohibition Party—the oldest, most neglected third party still in existence in the U.S. Corrigan’s platform proponed collective bargaining, fiscal conservatism, the establishment of better services for veterans, and more. Despite campaign materials boldly suggesting that few could better embody the American Way than “Wrong Way” Corrigan, he garnered only a disappointing 1.62% of the vote.

|

| Campaign Button for Douglas Corrigan, 1946 Unknown Maker; California Celluloid and metal; 1 1/2 in. 85.35.13 Gift of Mr. Neal Machander |

Citrus Groves and Fields of Green

Corrigan retired in Santa Ana with his wife Elizabeth only a few blocks away from the museum. They had jointly purchased an 18-acre orange grove off Flower St. and Orange Ave from a C.C.L. Leslie who had planted it in 1910. Without any expertise in citrus cultivation, the two did just that until Elizabeth’s passing in 1966. Corrigan continued to work the orchards for another three years, but ultimately decided to sell them, keeping only the house on the property. He became increasingly reclusive in his later years; a Los Angeles Times article published on the 50th anniversary of the feat described him as “more crusty than feisty” and suggested that he “prefers his own company as a man made a loner by private sadness—yet remains a blarney-stuffed, rule-bending bantam.” Corrigan now rests at Fairhaven Memorial Park in Santa Ana, the same cemetery in which the founders of this museum are buried. Sunshine and the legacy of an Irish American pilot defying all odds and a government bureau to return to his sire-land live on at the Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California.

Text and images may be under copyright. Please contact Collection Department for permission to use. References are available on request. Information subject to change upon further research.

Comments